I met a neuroscientist at a party recently. I arrived early, half an hour after the invitation’s stated start time. I’m very uncool in that way. He and his friend, only slightly cooler, sat down at the banquette next to me, and ordered dozens of oysters. He insisted I have one.

Naturally we got to talking—he’s from Rome, his friend from Fort Worth. A Dallas girl myself, I flashed my pearliest Chi Omega smile and attempted to engage his older, gayer companion in some hometown small talk. He frowned, blew me off, excused himself from the table. Utterly disenchanting, I had stolen his date.

I tried out my new bit when the man from Rome asked what I do for work: “Nothing!”

“Come on, you’re teasing me.”

“I’m a writer. You?”

“I study neuroscience, I mostly do research.”

Pain and surprise are his areas of focus. Pain and surprise…brilliant. What a romantic and sensical application of science! He is in New York only briefly on sabbatical, which I always understood to mean a break from work. For him, it is an opportunity to do more work—from Columbia to Harvard to Yale to NYU, guest lecturing and doing whatever else a romantic neuroscientist does.

Finally, an opportunity to discuss a topic of great personal import with someone who would surely understand, “What are your thoughts on ketamine?”

“I’m somewhat familiar with its applications...”

I was, in fact, high on ketamine at that very moment. It was administered under my doctor’s supervision at a reputable clinic earlier that afternoon. I do not, and will never, do it recreationally. But boy is life fun after having 90ml of sweet dissociative release pumped directly into my bloodstream. He mustn’t know.

“Do you know Dr. M at McLean? He runs the ketamine research program.” Excellent choice, to name the one person I know (met once) in academia. It’s a small world, is it not?

“I do not. Is he a colleague…? A friend of yours?”

“No, not at all. I interviewed him on my podcast about ketamine therapy for depression.”

“Podcast... I keep hearing about ‘podcasts.’ And you are the host?”

He seemed too impressed, apparently under the assumption that podcasts are something that you’re chosen to do by a legitimate media outlet, and not the audio equivalent of having an Instagram account. How could such a genius man be so ignorant about the current state of digital media platforms? Marry me.

We talked about his upcoming art tour of Texas, and I insisted he visit the James Turrell structure at Rice, and twelve-year-old Michelangelo’s first ever painting—a gory and colorful depiction of The Torment Of Saint Anthony—at the Kimbell. He circled back on my writing. Apparently part of some imperial academic cabal, he mentioned his dear friend, the Pulitzer-winning author, “You would love her.” God, what have I done? In meeting men I usually try to front load with red flags, not deceive them into some fantasy that I am particularly well educated or especially classy; that I would not be returning home in mere hours to watch South Park reruns through a dubious LED light mask until the guanfacine tablets and indica gummy kick in for a light four-to-six hours of shallow sleep.

At that point I did something strange, especially given my general distrust of Italian men: I texted him the pitch for my novel. It was a neat little pdf containing a few impressive-sounding sentences about me, an overview of the plot, and two excerpts. Then my friends finally arrived with all the other naturally cool New Yorkers, and I was sucked into the martini-swilling horde.

The next morning I awoke to the most enthusiastic, thoughtful review of my writing—a reminder that I’d betrayed myself by sending this most sacred text to a complete stranger the evening prior. I never let anyone read my writing anymore. Who even was this guy? Seriously, what was his name? I hadn’t a clue.

I did agree to meet him the following Friday at the Italian coffee shop down the street from my apartment. “They have excellent raspberry bombalonis.” It must have been like someone in Rome proudly taking me to the local McDonald’s and insisting I try the nuggets.

“Bomb-o-loni. Plural has no ‘s.’”

“Sorry. I have to warn you—if I come off stupid, it’s because I had a brain injury a few years ago.”

“Piccola!” He studied the curve of my skull with concern. “Ah, you are teasing me again.”

“No, that’s actually true. I am worried you’ll find me dumb. You’re a neuroscientist and I—”

“You have a podcast!”

“Precisely.”

“And you talk with your guests about medicine?”

Sweet angel. I explained that the podcast is about beauty. Makeup. Fragrance. Industry news. I did reveal that I had done ketamine therapy in the past, hence the episode with my dear colleague, Dr. M. It’s always a risk to disclose. Laymen think you’re abusing horse tranquilizers under the guise of alternative medicine, and most MDs insist the research doesn’t validate ketamine’s new, vast applications for depressives. Italian MDs with PhDs in neuroscience think Americans are overtherapized, overmedicated, and basically need to get more comfortable experiencing life in full spectrum. Drowning in cognitive dissonance, I agree. We’ve commercialized feelings. If we don’t like the one we’re experiencing, we invent more and more efficient ways to change it to one more tolerable, and to charge others for it. It’s an unfair advantage in many ways, as is the case with all US healthcare. But a life without friction is that of a perpetual tadpole. A life of soothing treatments, to the point of eliminating any discomfort, prevents progress. Wasn’t it Satan’s self pity, in the form of his own tears and spittle created from sucking on Judas, Brutus, and Cassius like grotesque pacifiers in his three mouths, that dripped down, adding to the ice which kept him frozen in Dante’s hell core? Or do I remember that incorrectly?

Sensing my embarrassment, he shrugged it off, “I understand it’s quite a popular thing to do now.”

“Yes, but that’s what frustrates me—these people who just go in with no purpose other than to try it out for fun.” (Fucking Scott Galloway…) “The clinic I go to has a psychiatrist you meet with first, and an actual course of treatment is five-to-ten sessions, every other day. I did nine, because the first doses were ineffective.” I’m very special in that way, doesn’t he see?

He asked why I went in the first place. The reasons are impossible to explain to someone with so little time left on his visa. I felt the rush of hot tears well up behind my eyes and so I clenched my sinuses and gulped straight from the Acqua Panna in a desperate attempt to flush them back down. God how embarrassing, my cry reflex; to be so affected by something that will sound so shamefully trite to my own private Galen.

“I was in a lot of pain.”

“Wha?”

“I. Was. In. A. Lot. Of. Pain.”

“Pay-yan-e?”

“Pain.”

“Pain! Oh, pain, yes. You were…distressed.”

“Yes, pain! I thought you were an expert on pain.”

“That is not the type of pain I study.”

“Is there not a link between emotional and physical pain?”

“Yes, you are right. Chronic pain can lead to depression, absolutely.”

“But can’t the reverse be true? Can’t emotional pain also cause physical pain?”

He nodded in that agreeable, encouraging way a professor might, as if to say “it’s more complicated than that, but sure.”

“They don’t call it a distressed heart, they call it a broken heart.” I would win this debate through litigating colloquialisms, science be damned.

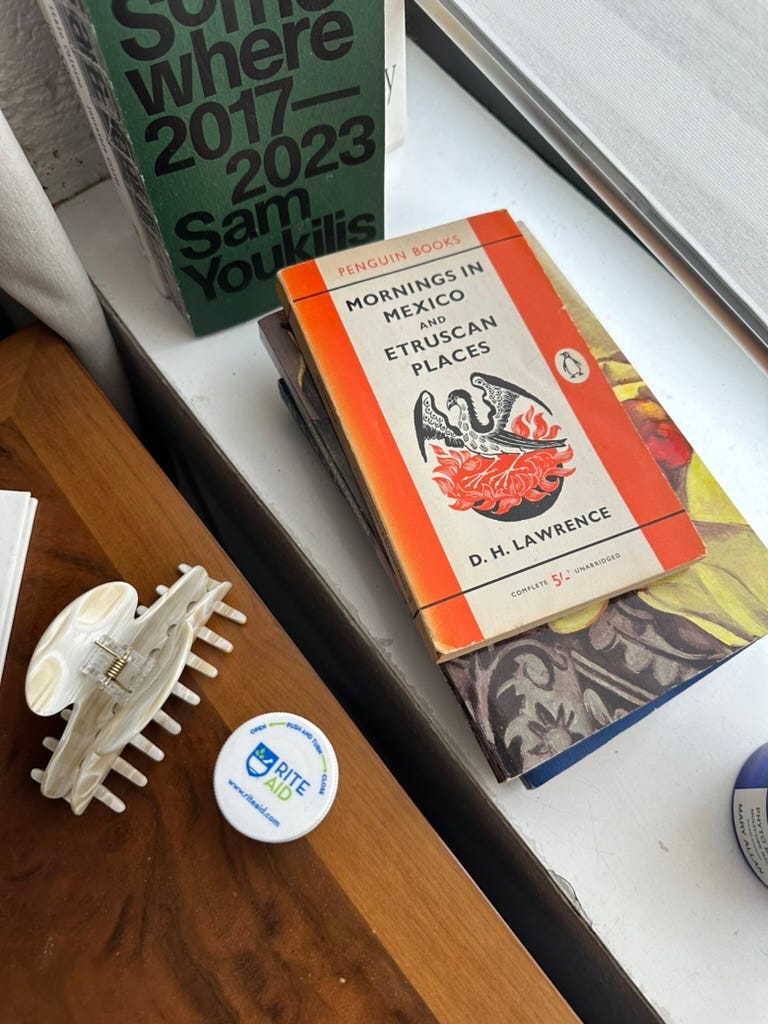

He reached into a deep jacket pocket and handed me a book—D.H. Lawrence’s Mornings In Mexico And Etruscan Places. Remembering my enthusiasm for Mexico City, something I’d forgotten we’d discussed that first night over oysters, he’d wondered had I already read it? Of course not, but feigning that possibility was as considerate as the gift itself. I suspect he compensates for his profession, which requires administering precise doses of pain to human subjects, by being so startlingly kind. Pain and surprise.

We went to the opera (an Italian opera, though he prefers German), we shared waffles (Belgian), we shopped at Left Bank and Bookmarc. We watched a documentary about the Roman art historian who planned to kill both Hitler and Mussolini in one fell swoop when forced to be their personal tour guide around Italy. He didn’t go through with it, but isn’t that amazing?

He went on his trip to Texas and expressed doubt regarding the authenticity of young Michelangelo’s painting at the Kimbell—my defense of which has strangely become an endless, thankless task against every art-loving man I know. When he was back, I showed him all of my other books, and my Helmut Newton prints (just pages cut from a damaged copy of his oversized SUMO book, though they look impressive framed). I asked if he knew my friend’s husband, Simone? From Blonde Redhead? He’s from Italy, too. (No.) I showed him all of my makeup and fragrances and my collection of tiny, specific tools and gadgets I collect and keep in labeled drawers, and my antique vase covered with orange doves from a master glassmaker in Murano—Italian, was he not impressed? Also, here’s the knock-off of Picasso’s impish devil figurine I made when I had the membership at the ceramics studio. It was the only thing I made at the ceramics studio. The process requires too much commitment, and something always went wrong between the drying and the firing… making ceramics is nothing if not a series of painful surprises.

He insists I come to Rome this summer so we can eat at the places only lifelong Romans know about, and drive fast through the countryside to see the painted Etruscan tombs, like the ones in the book he gave me—in full color!—and then sail along the coast of Sicily, which he ensures is an effective treatment for major depressive disorder. Though I’m familiar with these machinations, oftentimes empty promises, from romantic men, this time there’s some urgency to commit. His sabbatical ends tomorrow, and then he’s back to Europe, where his life of permanence exists. His lab, home in Rome, his professorship in London with the flat in Notting Hill, his Sicilian sailboat, his wall-sized art pieces that need to be insured, his racing cars that he speaks about in a hushed tone because in his world it’s a bit of a brutish sport…

All of my things, my tiny gadgets, and my lipsticks, and my paperbacks, and every single one of my possessions can be disassembled, bagged, boxed, and carried—the collection of an interloper in my month-to-month apartment. Even my work, of little consequence to anyone and not tied to great scholastic investment, exists in some omnipresent ether, The Cloud (at least where there’s wifi). I’ve designed it that way, my little life of optionality—my malleable, absorbent dunnage which lessens the shock of surprises, avoids pain and prevents breakage. No commitments, nobody counting on me, no one to disappoint and no one to disappoint me. Still, if life becomes intolerable—a measure which is lowered with each available treatment, each magical distraction—I have an easy out. How American. I can pack up and move neighborhoods to avoid seeing people I would rather not, I can get on a plane and leave for weeks without having to notify a single soul. I don’t even have plants to water. Going to Italy for the summer with this relative stranger would have the same impact on my chemistry as ketamine—a dissociation from the discomfort of reality, for one which is not mine.

For me it seems that staying put is progress.

This shot into my inbox and completely altered the course of my day.

I would definitely go